Highlights

- The US government has plenty of “reasonable” targets for tariffs. Canada is not one of them.

- China is the main source of global trade imbalances, pushing excess exports on both the US and Canada.

- The emerging trade war will damage both the US and Canadian economies, with very limited upside for the US government.

I am not of the breed of economists who view all tariffs as unpardonable acts of treason to the memory of Adam Smith. Trade policy is a handy tool of economic and political management. It is a useful complement to fiscal, regulatory and monetary policy. History is filled with examples of trade restrictions successfully employed to incubate industries, bolster national security and punish bad actors abroad.

If the Trump administration wanted to run a purposeful tariff strategy, there would be no shortage of worthwhile targets. In Trump’s first presidential term, China was the central focus of US trade policy. Switching tariff heat from China to Canada in Trump’s second term defies logic. China is the primary driver of global trade imbalances, while Canada suffers from the same force-feeding of imports that burdens the US economy.

China’s economic model partly relies on subsidizing exports through cheap government loans and an artificially weak yuan. Without this aggressive strategy of dumping subsidized manufactured goods on other countries — mainly the US, but including Canada — the Chinese economy would struggle to meet the 5% GDP growth target set by the government. Our June 2024 commentary warned that China would lean hard on subsidized exports to achieve growth.

The US bilateral trade balance with China has, admittedly, narrowed over the past decade. The merchandise trade deficit with China is down from 2% of GDP at the start of the first Trump administration to 1% of GDP today. This statistical narrowing could explain why Trump has gone easy on China — relatively speaking — in trade matters. But the observed decrease in US-China bilateral imbalance is all smoke and mirrors.

Chinese exporters are simply making use of re-exporting hubs, such as Vietnam, Mexico and Singapore, rather than sending widgets directly to US ports. Suppose China subsidizes a company to produce a smartphone. That smartphone is then shipped to Mexico, where it is finalized and repackaged, and ultimately trucked off to an electronics store in the US. US statistics tally that smartphone as an import from Mexico, which widens the US bilateral trade deficit with Mexico. But make no mistake, the source of the imbalance is Chinese economic policies.

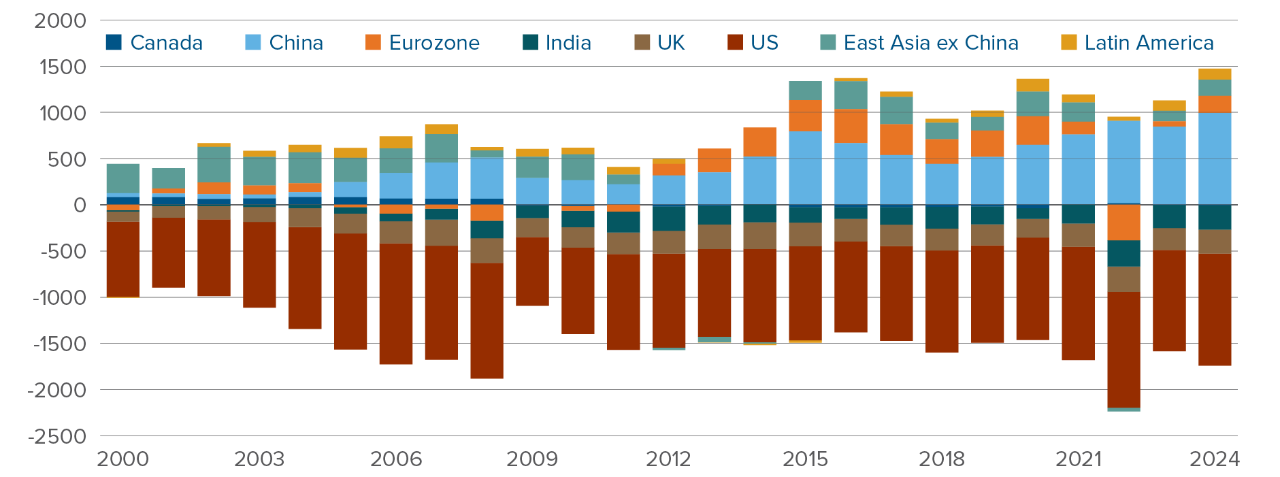

China sells, the US buys

Trade balances by country/region, billions of constant 2024 USD

Source: Bloomberg. The “East Asia ex China” grouping includes Taiwan, Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia. The dollar amounts are deflated using the US consumer price index, to convert balances into constant 2024 USD.

Source: Bloomberg. The “East Asia ex China” grouping includes Taiwan, Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia. The dollar amounts are deflated using the US consumer price index, to convert balances into constant 2024 USD.

China’s trade surplus in goods amounts to 2% of world GDP, approaching never-before-seen territory. Maybe the surplus goods aren’t flowing directly to the US. But they eventually end up there: the US is the only consumer pool large enough to absorb China’s exports, although the UK is certainly pulling its weight.

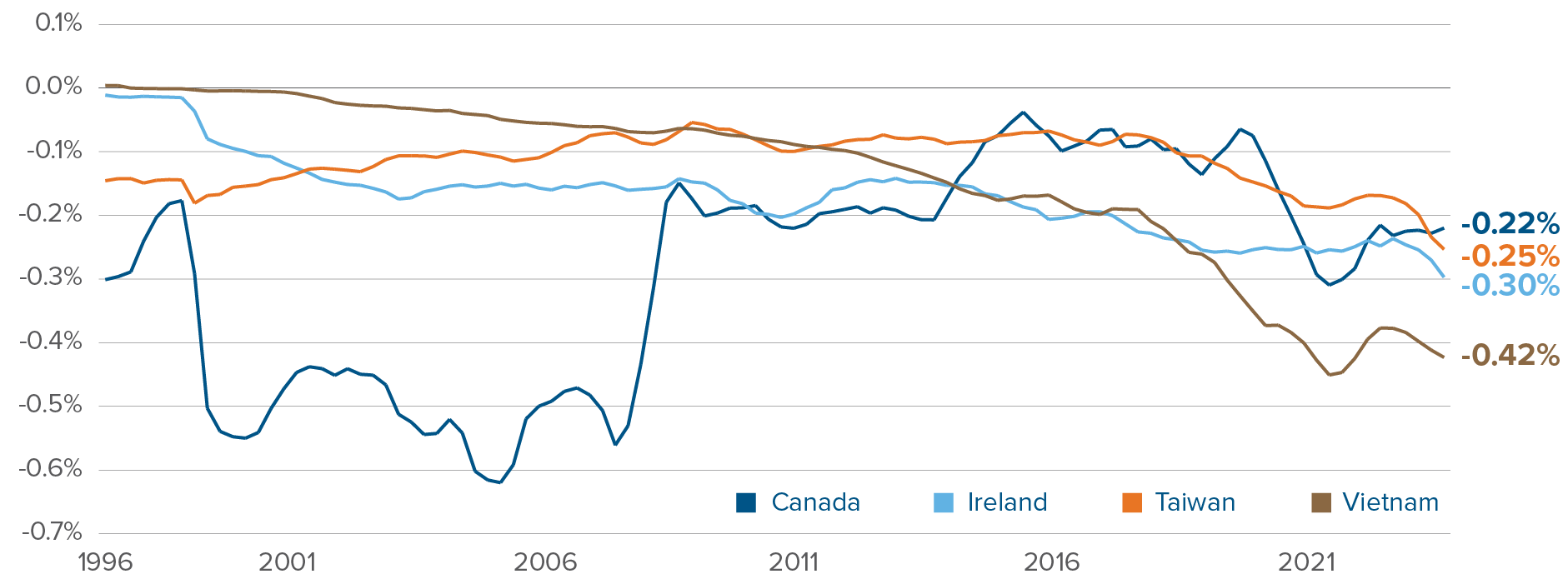

China is not the only reasonable tariff scapegoat for a confrontational US President, even though it is certainly the largest. Targets abound. The US trade deficit with Vietnam has blown up in recent years, the southeast Asian country being a key cog in Chinese trans-shipments to the US, facilitated by an artificially cheap currency. Taiwan also operates a not-so-subtle strategy of suppressing its exchange rate to boost exports, a practice repeatedly denounced by previous US administrations. Ireland’s low taxes have attracted the offshoring of large American pharmaceutical companies over the past few years. These multibillion-dollar companies pay close to zero corporate income taxes in the US, even if the country accounts for most of their sales.

Hey, Mr. President! Look over there!

Trade balance with various countries as a share of US GDP

Source: Bloomberg and Brad Setser, Council on Foreign Relations.

Source: Bloomberg and Brad Setser, Council on Foreign Relations.

The US government could also weaponize its trade policy to exert pressure on geopolitical adversaries. Threatening trade restrictions on those countries bucking US sanctions by buying Russian and Iranian crude — India, Turkey, China — would put additional pressure on these two warmongering oil exporters.

Canada is far down the list of “reasonable” tariff targets for the Trump administration. Last month’s commentary emphasized the inconsequentiality of the US trade deficit with Canada. This time, I'll take it a step further: Canada’s overall merchandise trade balance is much lower than it should be. As an oil- and mineral-exporting country amid an economic slump, Canada should be running a sizable trade surplus! If economic logic were respected, Canada should currently be exporting more than it is importing. Instead, Canada is running a small overall trade deficit.

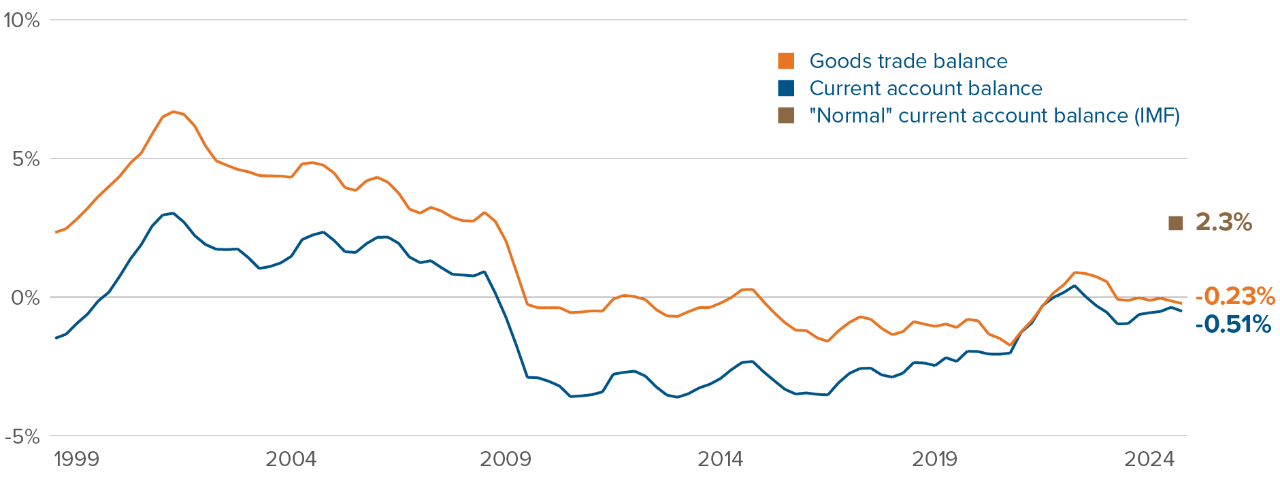

Canada’s trade balance is “too weak”, not too strong

External balances, % of Canada GDP

Source: Bloomberg and International Monetary Fund (IMF). Both lines show the rolling four-quarter balances as a share of GDP. The “normal” Canadian current account balance estimate is from the IMF’s 2024 External Balance Assessment.

Source: Bloomberg and International Monetary Fund (IMF). Both lines show the rolling four-quarter balances as a share of GDP. The “normal” Canadian current account balance estimate is from the IMF’s 2024 External Balance Assessment.

The International Monetary Fund estimates that the current account balance for Canada — a broader measure of external balance that encompasses merchandise trade — should be around 2.3%. At -0.5%, Canada’s current account balance is far below its “normal”, expected level. Trump’s denunciation of Canada artificially boosting its exports is upside down: Canada is not the source of US deficits. Rather, it is subject to the same deficit-boosting forces as the US. Export-subsidizing countries — China, Germany, Vietnam, Taiwan, etc. — push manufactured goods onto global market. We buy them, in exchange for our government bonds, real estate and overvalued equities.

In a different world, Canada would be working side-by-side with the US to rebalance global trade. If the US government really wanted to reduce the country’s massive trade deficit, it would narrow its ballooning federal budget deficit and turn the screws on trade offenders. Even if the US eventually “wins”, a trade war with Canada wouldn’t reduce the US trade deficit and could only hurt the US economy.

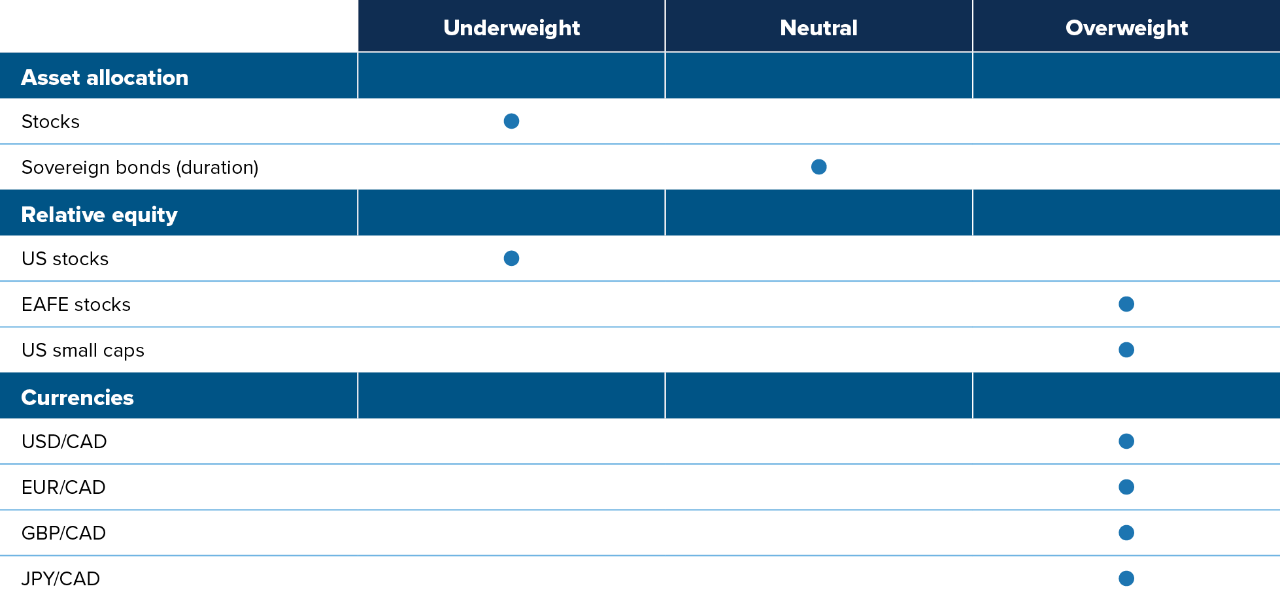

Multi-Asset Strategies Team’s investment views

Tactical summary

Source: Mackenzie Investments.

Note: The opinions expressed in this piece reflect short-term tactical views, which inform the positioning of some of the funds managed by the Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

Source: Mackenzie Investments.

Note: The opinions expressed in this piece reflect short-term tactical views, which inform the positioning of some of the funds managed by the Multi-Asset Strategies Team.

Positioning highlights

Neutral on duration: Our bond exposure peaked in early January, but after a rally in bonds mainly driven by weak US growth data, we are back down across the threshold to neutral in our positioning. Trump’s economic policies — government job cuts, trade wars, general uncertainty — will weigh on economic growth, but much of that effect has been priced in, with markets now expecting three Federal Reserve cuts this year. Trade tariffs will cause prices to jump in the US but are not an inflationary shock. Once the one-time effect on prices has passed, future inflation could be lower than without the tariffs, given trade wars could depress economic growth.

Overbought global stocks: We are bearish global equities for the second month in a row, after stock market gains — without a coincident improvement in fundamentals — finally brought valuations to overbought levels. We still think global economic growth will be fine and investor sentiment remains positive. But the growth in sales and profit margins required to justify current valuations is too ambitious for our taste.

US stocks running out of steam: After a historic run, US stocks have seemingly run out of steam. Their valuations are not at extreme levels, but they are pricier than most other equity markets globally — Canada excluded, notably. Plus, sentiment has recently shifted against US stocks: informed investors have been slowly turning away from the market since the end of 2024. Finally, earnings and sales revisions for the S&P 500 have turned sharply lower in recent weeks. International equities offer a more attractive risk-return trade-off in our view.

Canadian landing: After having an argument for the most disappointing advanced economy last year, Canada saw its economic data solidify in recent months. In a world without a trade war with the US, Canada’s growth slump would be receding, the job market would be on a durable uptrend, and the Bank of Canada might be done cutting rates. But that is not the cruel world we live in. In our view, the US will maintain tariff pressure on Canada throughout the next few quarters. The Canadian dollar will have to weaken even further to help the economy absorb the heavy blow of tariffs.

Defensive sectors shine bright: We generally like the defensive sectors of the S&P 500, including Staples, Health Care and Real Estate. They have attractive valuations after a few years of underperforming the broad index, and would benefit from the elevated macro uncertainty and slowing economic growth we expect for the coming months.